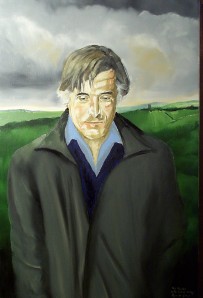

As well as being a poet of the highest order, Ted Hughes was an early advocate of neo-Shamanism, an environmental campaigner, a pagan animist, and an astrologer. He is celebrated as an influential eco-poet whose work combines exquisite naturalistic observation with an encyclopedic knowledge of lore, mythology, and esoteric traditions. He also happens to be an important ancestral presence here in the Calder Valley, where I’ve spent the whole of my adult life. So I often find myself walking in places he wrote powerfully about.

Ted Hughes’ life story has, of course, been tangled in controversy since the suicides of Sylvia Plath, and then of his subsequent partner, Assia Wevill. When I worked for a psychiatric survivor led voluntary organisation I had a copy of Sylvia Plath’s ‘The Hanging Man’ on the wall behind my desk. Ted Hughes endorsed her description of her encounter with modernist psychiatry as a grotesque parody of shamanic initiation, refused to medicalise her distress and madness, and supported her through the night terrors of its long aftermath. I count myself amongst those readers who empathise with both Hughes and Plath, whilst recognising that both were human-all-too-human. The hubbub of partisan biography shouldn’t distract us from appreciating and critically responding to Ted Hughes’s considerable achievements as an eco-animist poet.(1) Nor should it prevent us from acknowledging that not all of his enormous ouvre is wonderful, and that there are a few problematic moments.

In her recent book The Bioregional Economy, Molly Scott Cato uses Max Weber’s influential critique of the disenchantment of the world. After the protestant reformation God became wholly transcendent and otherworldly, and magic was banished from everyday life. Once the world had been constructed as mechanical it could be rendered as raw material for capitalist exploitation.(2) Reviewing Max Nicholson’s The Environmental Revolution in 1970, Ted Hughes made much the same argument. “The fundamental guiding ideas of our Western Civilization … are based on the assumption that the earth is a heap of raw materials given to man by God for his exclusive profit and use. The creepy crawlies which infest it are devils of dirt and without a soul, also put there for his exclusive profit and use. By the skin of her teeth woman escaped the same role”. The mediumistic artist, however, may be able to see ‘the draughty radiant paradise of the animals’, even Pan, ‘the vital, somewhat terrible spirit of natural life, which is new in every second.” Some of what he wrote in that review, more than forty years ago, could easily be mistaken for the work of a contemporary animist: “…while the mice in the field are listening to the Universe, and moving in the body of nature, where every living cell is sacred to every other, and all are interdependent, the Developer is peering at the field through a visor …”.(3)

Not surprisingly, many critics describe Ted Hughes’ work as biocentric, and discuss his belief in ‘the shamanic healing power of poetry for a species alienated from its natural home’.(4) When Hughes was appointed poet Laureate, his friend Seamus Heaney proclaimed him ‘shaman of the tribe’. As a young man, Hughes had a visionary dream in which a theriomorphic fox figure came to him. He recounted this experience in The Thought Fox, and may well have understood it as a threshold call.

The remarkable Cave Birds sequence evokes a male protagonist’s spirit journey through an underworld where he’s confronted by his own past, experiences judgement and dismemberment, marries a female figure who is both his ‘anima’ and the Goddess as Nature, and is eventually reborn. The extra-ordinary power and beauty of these poems came into focus for me when I read some of them to my friend Peter during the last year of his life. Terry Gifford regards Cave Birds as an exemplar of post-pastoral poetry, a key feature of which is that it attends, with a sense of awe, to the destructive as well as the creative aspect of Nature. This perspective contrasts with that of some earlier critics who discuss shamanism in transcendental and dualistic terms.(5). I’ve been re-reading Ted Hughes’s poems to see whether some of his underlying assumptions, notably his adoption of Jung’s essentialist conception of generic feminine and masculine principles, and his veneration of a Gravesian Goddess, get in the way. For me, they mostly don’t seem to.

Ted Hughes said that angling connected him with ‘the stuff of the Earth, the whole of life’.(6) Leonard Scigaj talks about Hughes’s ‘ecological animism’ in relation to the hydrological cycle.(7). If you read Flesh of Light, The River, or October Salmon, you’ll see why. Although Hughes may have been influenced by Mircea Eliade, his take on shamanism was always grounded by his fascination with, and respect for, flesh and blood animals, and by his concern with human healing. His belief in the ‘real summoning force’ of poems, the capacity of carefully charged words to reach out and connect with non-human animals, resonates closely with David Abram’s account of shamanism as a process of relationship with more-than-human worlds.(8)

From my own practice I can confirm that such ‘showings’, as I like to call them, do happen from time to time. Hughes may have exaggerated the power of poetry per se, but he was certainly not succumbing to the ‘pathetic fallacy’ (falsely imagining that Nature was responding to his inner states). His own poetry drew upon an exceptional pool of life experience, and was often crafted with specific ‘spiritual’ and/or magical intent. Ann Skea refers to his shamanic poetic magic, and locates him in the British bardic tradition.(9) Jeanette Winterson writes: “the wild creature circling the tamed world comes as unknown energy, sensed but not seen. The bound of the animal out of instinct and into consciousness, its ‘hot stink’, is what makes the poem happen. For Hughes, poems happen in this meeting/mating between very different measures of energy – the raw feral of the instinctual life, and the channelled potency of consciousness.”(10)

Ted Hughes’s poems can be difficult, sometimes because of their complexity, sometimes because of their unflinching directness. Alice Oswald comments “the disruption of comfort, the chance to concentrate utterly on what’s there, to see it in its own way and to say so without disturbing its strangeness is what Hughes’ offers”.(11) Terry Gifford reports that he’s seen people in the audience faint when February 17th is read. Transcribed from Ted Hughes’s farming notes, it records an occasion when he had to cut the head from a lamb that had been strangled during birth, in order to save the mother. I’m reminded of Graham Harvey’s pointed query as to why, when there are so many urban workshops on shamanism, there are none on Pennine shepherding, or its associated religion.(12)

I recently went to an event in Ilkley commemorating the inaugural performance of Cave Birds there in 1975. Keith Sagar, a literary critic and friend of Ted Hughes, who had been in dialogue with him during the writing of Cave Birds, and who was to have given the talk, had just died, so the event became a fitting tribute to him.

I’d been wondering whether the 1975 performance might have been, in some sense, a shamanic event. Michael Dawson, who had commissioned Cave Birds, explained that the poems were read by actors who picked the running order ‘randomly’ from a box on the stage. When a recording was played, I found that their declamatory Thespian style, booming across the years, didn’t work for me. Something seems to have worked for one audience member at the time though. Suddenly the reading was interrupted by a protracted and full blooded scream, emitted by a woman at the back of the auditorium, who, we were told, also vomited in the foyer. The performers on stage assumed this had been a theatrical stunt, so continued as though nothing had happened.

The woman in question, who turned out to be one of Keith Sagar’s adult education pupils, reportedly laughed about it afterwards, and said the ‘involuntary howling’ that came upon her gradually had been triggered by one of the Leonard Baskin bird figures that were being projected on stage. Ted Hughes later wrote about Baskin’s prints that it was ‘as though a calligraphy had been improvised from the knotted sigils and clavicles used for conjuring spirits’. This trace element in his draughtsmanship suggested a psychic proclivity, ‘a passport between worlds usually kept closed to each other’.(13) It also seems likely that the text of Cave Birds, evoking, as it does, the primal mysteries of birth, embodiment, death, and an afterlife, and our attendant human fears and disorientations, contributed to her reaction. Strangely, the opening poem in the Viking Press edition of Cave Birds is called The Scream, and ends with a vomited scream. The poem had already been written at the time of the 1975 performance (14), but I’m not sure whether it was read on stage at Ilkley that evening.

Whilst this occurrence undoubtedly attests to the potential power of the poems and images, the event clearly hadn’t been, and almost certainly couldn’t have been, conceived as a shamanic performance (where provision would have been made to assist participants in negotiating their experience). Following the 1970 publication of Arthur Janov’s Primal Scream, ‘therapeutic’ screaming was in the Zeitgeist at the time. As someone who used to faint in cinemas, and on one occasion (in the late 60’s) refused an invitation to stay and discuss my needle-phobic reaction with an entire audience of film-goers, I have some sense of the difference between artistic and therapeutic environments, and of the ethical considerations that arise in respect of the latter. Whatever happened that night in Ilkley, I can vouch for the consciousness-deepening and healing effect of many of Ted Hughes’s poems, when read in conducive circumstances to the right person. When my friend died last year, I read A Green Mother, over and over. It had been one his favourite poems. Often tears came before they’re mentioned in the last line. I was, of course, reading it from an earth-centred animist viewpoint, for someone who would have been excited to become a flower, a bird, or a worm.

B.T 7/11/13.

Here is a link to the final draft of Shaman of the Tribe, Ted Hughes and Contemporary Animism that appeared in the Journal of the Ted Hughes Society in 2014.

See also a series of posts entitled Notes From the Tuning Fork, Ted Hughes and the Calder Valley.

Ted Hughes, Collected Poems, Faber and Faber, 2003.

Christopher Reid, ed. The Letters of Ted Hughes, Faber and Faber, 2007.

Ted Hughes, Cave Birds, An Alchemical Cave Drama, Viking Press, 1978, with drawings by Leonard Baskin.

Keith Sagar, Ted Hughes, Gaudete, Cave Birds, and the 1975 Ilkley Festival.

Other Sources:

1) Neil Roberts, The Plath Wars, in Ted Hughes, A Literary Life, Palgrave MacMillan, 2007.

2) Molly Scott-Cato, The Bioregional Economy, Earthscan/Routledge, 2013.

3) Ted Hughes, The Environmental Revolution, (1970) in Winter Pollen, Occasional Prose,, ed William Scammell, Faber and Faber, 1994.

4) Terry Gifford, Ted Hughes, Routledge, 2009.

5) Terry Gifford, Pastoral, Routledge, 1999.

6) quoted in Neil Roberts, Ted Hughes, A Literary Life, Palgrave MacMillan, 2007.

7) Leonard Scigaj, Ted Hughes, 1991, quoted in Terry Gifford, Ted Hughes, Routledge, 2009.

8) David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous, Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World, Vintage, 1997.

9) Ann Skea Ted Hughes, The Poetic Quest, University of New England, 1994, and website.

10) Jeanette Winterson, Foreword to Great Poets of the Twentieth Century, No 5, Ted Hughes, The Guardian / Faber and Faber, 2008.

11) Alice Oswald, Guardian, 3/12/05, quoted by Terry Gifford, ibid.

12) Graham Harvey, Listening People, Speaking Earth, Contemporary Paganism, Hurst and Co, 2007.

13) Ted Hughes, The Hanged Man and the Dragonfly, Note for a Panegyric Ode on Leonard Baskin’s Collected Prints, in Winter Pollen, Occasional Prose, ed William Scammell, Faber and Faber, 1994.

14) Ann Skea, pers comm.

Thanks for sharing this, off to read Cave Birds in a new light…

I had no idea. Thank you!

Fascinating analysis of this poet, of which i know nothing and will now have to investigate. Its tragic how so many around him ended their own lives and makes one wonder if he had not died of natural causes how his own life would have fared. Regarding the quote “the ‘pathetic fallacy’ (falsely imagining that Nature was responding to his inner states)” is that something you believe or from Ted’s writings? I have not had the animist “showings” you have had but some glimpses of the fey, especially in the sound of running streams. I think i believe part of it is my mind reaching out to and putting a face on a force in nature and the other part is nature showing a face back that a human can relate to. The article you wrote “Ted Hughes – Shaman of the Tribe?” is excellent also. Thank you.

Ted Hughes was, and still is, a towering public literary figure here in the U.K. He got a bit of a bad press in the U.S, often unfairly I think, so may be less well known there? Here in the Calder Valley he remains quite a powerful presence, in various ways, at least for some of us. The term ‘pathetic fallacy’ (from ‘sympathetic’) came to mind because its a convenient way of dismissing the kinds of experience that Hughes clearly had (e.g the appearance of those flies, and that otter, mentioned in the article. His approach to fishing, etc). I like your idea of nature showing a face back that a human can relate to. (when light catches a stone, for example?). But sometimes there’s also a sense of the agency of particular presences or ‘people’ too. For me its less about particular words, than the heart, – at best its a love relationship – plus a clear intention to communicate, feeling o.k when it doesn’t seem to ‘work’, trusting in the possibility, and doing something in return for the species/land. Ted Hughes campaigned impressively against river pollution.

Going back and reading Cave Birds has put me in awe of how Hughes’ poetry is both completely grounded in the rawness of nature and the flesh yet utterly hallucinatory and visionary at the same time. This time round the image of the Interrogator really stuck in my mind along with ‘small madness of roots… mineral stasis… rain’ and of course the goblin rising up at the end. Amazing 🙂